Although studied primarily by the students of Urban Planning, the concept of a ‘15-minutes city’ is taking today’s fast-paced world by storm. To put it simply, a 15-minute city is an urban concept where residents can accomplish or access all their daily necessities in less than 15-minutes, but by either walking or cycling from their homes. Despite appearing to be seemingly far-fetched, it is quite realistic, achievable and frankly voluntary on the part of the individual citizen without any additional cost attached. This is giving rise to a wave of expectations regarding increasingly proliferating rapid 10-minute deliveries by many E-Commerce and E-Retailers. The unbeatable convenience of rapid deliveries is evident in Europe and the United States, where companies such as Turkey's Getir and Germany's Gorillas are expanding fast to satisfy the rising expectations from contemporary customers.

The race for 10-minute delivery: Who all are in competition?

Despite being in its nascent stage, the quick delivery market is flooded with players looking to acquire a competitive advantage in an already crowded marketplace. As activity grows, research firm RedSeer has claimed that India's quick commerce sector, worth $300 million in 2021, will swell 10-15 times to surpass $5 billion by 2025.

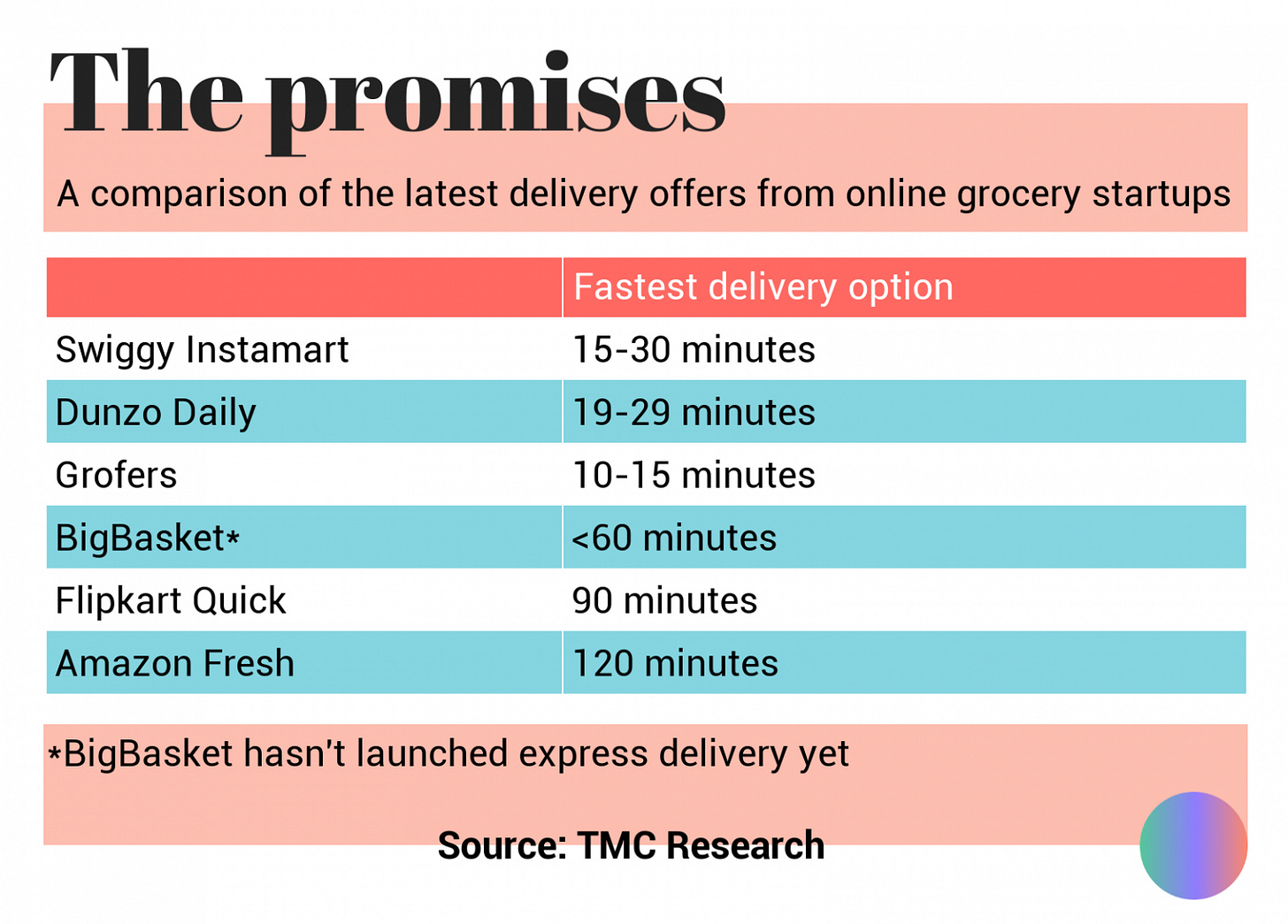

Zepto, a Mumbai-based instant grocery delivery startup, was founded by a couple of 19-year-old Stanford dropouts and has been valued at $570 million after being backed by investors such as U.S.-based Glade Brook Capital. Blinkit calls its service "indistinguishable from magic" and says it wants to become a $100-billion business. India's largest offline retailer, Reliance, said that it wants a piece of the quick delivery market space, when it invested in Dunzo, another Indian startup that runs a 19-minute delivery service. In fact, Reliance teased about offering delivery services from the stores they own and run offline in 20-minutes, going forward. With the likes of Amazon, Tata, Walmart, and Grofers competing with each other; only time will tell whether this is an attractive market or a soon-to-burst bubble.

Is there a need for 10-minute delivery?

The escalation in ETAs is significant, as the delivery time has plummeted from a minimumof 4-6 hours in 2019 to merely a few minutes in 2022; deliveries that were transferred to the next day for orders made in the evening are now primitive as customers can now avail the 10-minutes delivery service as late as the primetime.

Online grocery penetration is expected to reach ~3-5% by 2025 from less than 1% in 2021. Long-term structural drivers remain strong – rising income and affluence, lower-tier consumption, E-Commerce penetration (growing at ~30% CAGR) and a young population (~50% below 25 years). Grocery spending as a proportion of income continues to remain high at ~ 30%.

From the customers’ perspective, they already have companies willing to deliver in 20-minutes to 4-hours, and therefore, if they are opting for a 10-minutes delivery, it must be the urgency dictating the order, or because they accept paying a higher fee for faster delivery. However, what the customers do not realize is that, in most cases, they are being sold a marketing gimmick, not a quick delivery service. These naïve customers do not comprehend that for the prize of unprecedented happiness in their lives with 10-minutes delivery, too much investor money and delivery partner calories are being burned. An average customer anyways puts the quality of products, packaging, and delivery over the time taken to deliver, but again, in this brave new world, trends always seem to sell, even if their utility is somewhat questionable.

How is it executed?

Online grocery platforms are shifting from the marketplace model to build dark stores or hubs in proximity to consumers’ residences as in the former model the delivery speed slows down. A dark store is a large warehouse or a network of warehouses that stocks inventory to sell directly to its consumers. Grocery startups Milkbasket and BigBasket have implemented this model.

Distribution from dark stores will help startups gain control more on quality and experience fewer stock-out scenarios. Overall, by the time the order exchanges hands at the handover station, it would be just 58 seconds on average. With the click and collect model involved in dark stores, the startups get a clearer picture of stock levels and therefore have better product availability than a marketplace model. Here, the company does not need to spend on retail experience or store beautification. As a result, the cost is saved to stock more variety of items for less inventory. It improves distribution accuracy, avoids mix-ups, and solves perishability challenges, which are usual hurdles in online grocery delivery.

Unit economics

For express deliveries, let’s follow the riders to understand how the economics work. In a good month, a rider makes anywhere between ₹18,000-20,000, which comes out to be ₹600-660 a day. Let’s assume that the rider is working 12 hours on any given day (which tends to be the norm for full-time riders). And if they take one hour to make a delivery, that’s 12 orders in a day and so average cost of about ₹50-55 per delivery.

The basic delivery costs are not linear between, say, 45-minute and 30-minute deliveries. And it goes up even more sharply for anything that is below 30 minutes.

Both the margins and average order values in express grocery delivery are abysmal. In the case of 15 to 30-minute deliveries, you’d get orders that are largely top-ups; the basket size is just about ₹200-250, on average. And on that, the margins are less than 10%. So for a cost of more than ₹70, you are barely making ₹20. You could charge a delivery fee of about ₹25-30, but that still doesn’t cover the cost.

And as the delivery time goes down, other costs grow too. The lower the time frame, the greater number of dark stores are needed. For anything below 30 minutes, the companies need a dark store every 2-3 km.

Criticism

India's accident-prone roads make quick commerce a dangerous business. Even in cities, most roads are riddled with potholes, while cattle or other animals straying into traffic present a frequent challenge for motorists, who often violate basic rules. Quite a few delivery guys said they faced pressure to meet delivery deadlines, which often led to speeding, for fear of being rebuked by store managers.

In August, Blinkit's chief executive said on Twitter that riders were not penalized and could deliver "at their own pace and rhythm," as dark stores are always near destination sites.

Future - Is it fab or a fad?

In India, the trend is starting to catch on as consumer behavior evolves. Over the past few years, buying habits have shifted away from larger, monthly purchases to smaller, weekly ones. The number of single-person households interested in time-bound deliveries is increasing, as is unplanned ordering. Additionally, Covid caused online ordering to substitute some neighborhood Kirana store visits.

Incumbents in this space are still growing, still rebranding, still learning. It’s not just BlinkIt; Ola is going hyperlocal and Big Basket is pushing its express delivery service BB Now. It’s working, too. Grofers raised $120 million, co-led by Zomato, in June and may see another $500 million from them, Swiggy’s has earmarked $700 million for Instamart, and Ola, too, is reportedly earmarking ₹250 crore ($32.8 million) for its ‘Ola Stores’.

Meet the Author

This issue of Funnel Vision has been authored by Avichal Agrawal and Saurabh Laddha.

That’s all for this edition!

Do follow us on Instagram and LinkedIn. Stay connected for insightful articles lined up for this year.